There’s Usually A Very Good Reason People Won’t Admit They Made A Mistake

Despite all the talk about the beneficial effects for an organization in “failing fast” and the virtues of experimentation, that often doesn’t translate to encouragement of, or even tolerance for, mistakes made by employees. Why? Because while companies seem heroic in strategically “trying things,” making big bets, and flailing around till they get it right, employee goof-ups don’t seem consistent with overriding virtues of excellent customer service, one-and-done, and total quality that are burned into the tactical day-to-day work ethic of every business.

Consider the following case situation. I ordered some pipe fittings by phone from a supply house in Minnesota. They charged my credit card, shipped the parts out by one of the major carriers and gave me the tracking number.

According to the carrier’s system, my package was delivered to my porch the next day. The problem was, it wasn’t. I called their 800 number, the rep looked up my case and confirmed: Yep, your package was delivered to your porch. It says so right in our records.

So, I filed a claim. Three weeks later a letter from the carrier arrived, telling me again what they had already told me: My package had been delivered to my porch exactly on the date it was supposed to be delivered.

Something else arrived that day — weeks after the supposed delivery date: My package. Only it arrived in my US Mailbox, delivered not by the carrier who shipped it, but by the US Postal Service!

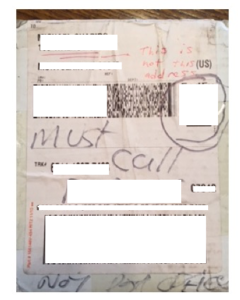

Sometimes a picture tells it best. Here’s what the front of my package looked like by the time it got to me.

It’s easy to figure out what happened: The package was delivered on the correct day — but to the wrong porch. The person who got it sent it to the US Post Office where he thought it came from, and wrote at the top in red ballpoint “This is not this address.” The US Post Office saw the tracking number, identified the carrier who had actually shipped the package and wrote in black felt-tip “Must Call (the carrier)” and “Not Post Office.”

The driver didn’t know he delivered it to the wrong address. And when questioned, he stuck to his original notation that he had delivered it to the right porch.

When I talked with the customer service rep, she proudly told me they have very strict quality control procedures in place and that “drivers are “dinged” (penalized) for wrong deliveries.”

Of course he said he did it right! With his livelihood on the line, he had no incentive to retrace his steps and see whether he really had delivered it to my place or whether he had been at the wrong house. The company’s system discouraged him from finding out the true state of affairs, and made it virtually impossible for him to admit he made a mistake! Here’s what was wrong:

- The company held a misguided view of how to encourage “right action” that led to the establishment of penalties as an incentive, and the driver’s consequent fear of making a mistake.

- The company’s policy was based on an unrealistic denial of the inevitability of mistakes.

- The company lost sight of the main purpose of the business: that the customer gets the package — and the primacy of the customer’s testimony as the last word as to whether or not that really happened.

- The company did not encourage its customer service reps to be curious problem solvers: Wasn’t anyone curious why I would say I didn’t get my plumbing fittings when the driver said they were delivered?

What incentives do you have in your system that invite bad behavior by employees that causes unintended consequences, and that ultimately frustrates the very purpose of your product or service?